Norway’s Other Favorite Fish

Aquatic butterflies or tiny baby halibut?

While salmon farms dominate the world of Norwegian aquaculture, another iconic species is on the rise.

Tag along with PJ Stoops, CleanFish’s Director of Research and Development, as he explores the where and why of halibut farming with a visit to Nordic Halibut’s facility in Averøy.

There’s enough light in the Nordic Halibut nursery to make out the contours of the room and the rows of tanks, but not enough to safely navigate without the aid of a headlamp. Each tank appears to be more than ten feet across, and about half that deep. The room itself is quiet save for the hum of pumps, filters, and feed dispensers. The two gentlemen tending the tanks move about as soundlessly as cats.

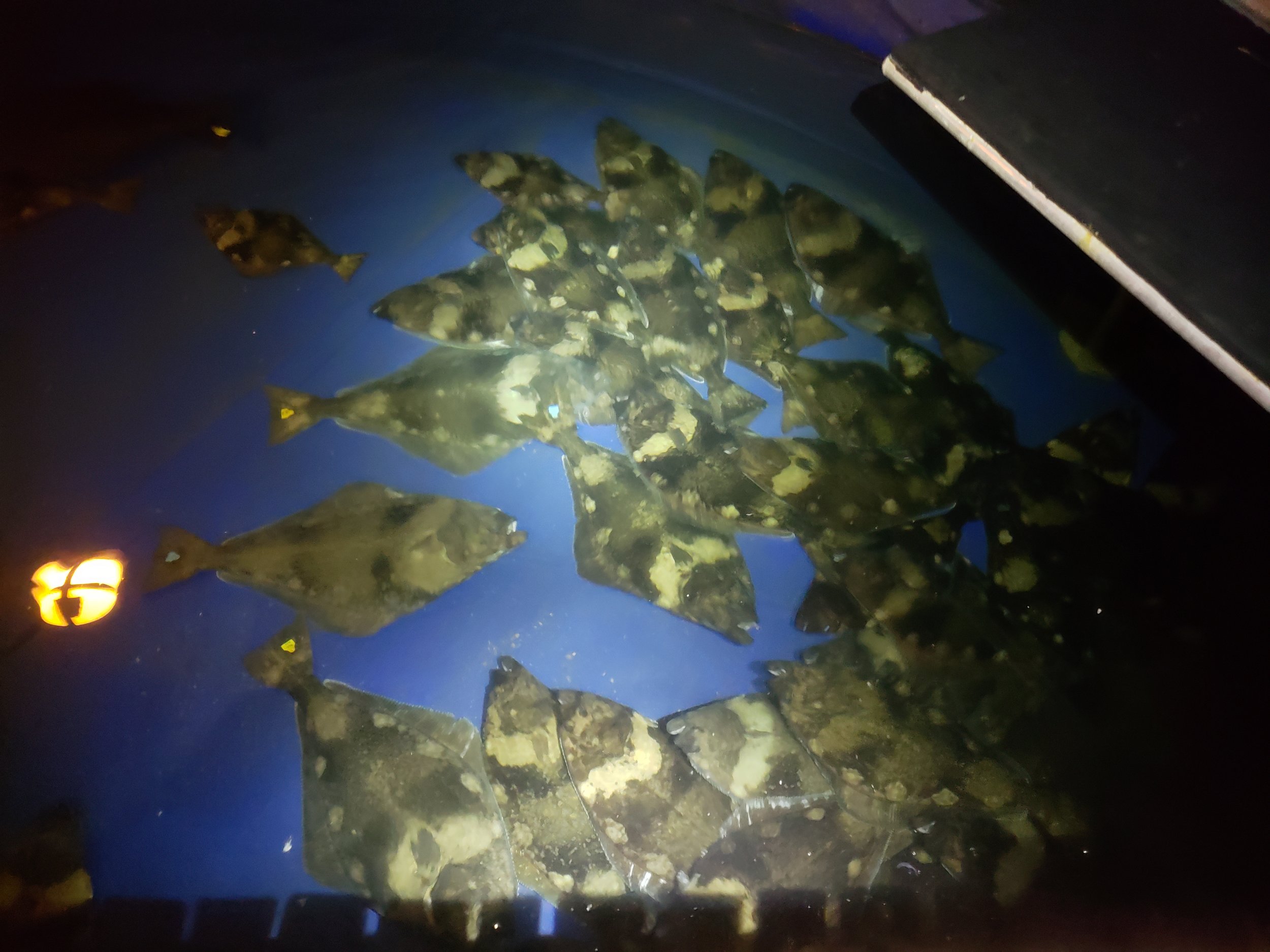

Through the pale light of the headlamps, the spectacle is almost disconcerting — a kaleidoscope of what appear to be aquatic butterflies, thousands of them, every last one a mottle of chocolate brown and aged ivory. Each weighs just a few grams, is about an inch long, and is more or less defenseless against anything bigger than itself. They are only a few months old, and, having passed through several post-larval stages, now look more or less familiar to anyone with a working knowledge of seafood. For these are Atlantic Halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus). Over the next several years, they will grow up to one thousand times larger than they are now (a similar feat by a human baby would result in a giant weighing around two and a half tons). Though their accommodations are spacious and provide perches and coves of various sorts, they prefer safety in numbers. So they generally crowd around one side of the tank, just sitting one atop the other, several deep, with a few recalcitrant souls flitting about the remainder of the space. People at the farm refer to the behavior as “stacking up.”

Over the next several years, they will grow up to one thousand times larger than they are now (a similar feat by a human baby would result in a giant weighing around two and a half tons).

As insignificant as they are now, they are giants compared to those in the next room. There, in tanks no larger than barrels, swim tiny larval halibut. They are barely visible to the human eye, and easily mistaken for bubbles. These are only about a month old.

The broodstock are in swimming pool-sized tanks in yet another room, this one even quieter than the others. These are large, fecund, and contented fish — all weigh several dozen kilograms, at least. While everyone at the farm works every day to ensure a high quality of life for their charges, the broodstock are afforded even more luxurious treatment. Though they represent semi-domesticated bloodlines, all of these fish’s ancestors once swam in the deep fjord just adjacent. They are truly Norwegian halibut.

Later, in other buildings on the edge of another fjord, are massive tanks, each maybe 30 feet across, and almost twice that deep. In these swim the juveniles, now the better part of a pound. They have lost their stark coloring, and are more or less a uniform sandy brown. No headlamps are necessary here. The cavernous buildings are instead imbued with just the shade of pale yellow light that these fish prefer.

Finally, there are the grow-out pens, clustered in three groups around two fjords. From the landlubbing human point of view, these pens are difficult to conceptualize, even when one is standing on one looking directly at it. It seems that we as humans don’t do very well with abstract ideas of volume (or at the very least, the human writing this doesn’t). From the surface, there is not much to see, for halibut don’t swim up very often. One discerns diamond-shaped shadows the better part of a hundred feet below, but little more. The fish in these pens will continue to grow for another year or two.

Ironically, unless one is willing to brave the frigid Norwegian waters, one has to be on dry land to see below the water’s surface. Every pen is fitted with cameras that capture everything from bottom of the net to the surface, and everywhere in between. From the control room, the gimlet-eyed Ann Kristin (who is more familiar with the pen operations than I am with my own house) sits in front of several screens, each split between several cameras. She pans here, zooms in there, pen to pen, up and down. To a layperson, it is a nonsensical, if utterly fascinating, display. But Ann Kristin is completely at home. With these cameras she makes sure the fish are fed enough, though without wasting feed. She checks on the fish (knowing from long experience what a contented halibut looks like). She inspects the pens themselves, ensuring that rigorous maintenance protocols are always followed.

In Norway today, one probably won’t find anyone worshipping halibut, but one easily finds devotees.

The Norwegian coastline (the second longest in the world, after Canada) is pockmarked with more than a thousand fjords, most of which are at least a few hundred feet deep and many miles long — a fact that allowed prehistoric peoples to target species that would not be common to most other peoples in Europe until about a thousand years ago. (Salmon, with its freshwater spawning strategy, is another kettle of fish.) The earliest middens (pre-historic landfills, more or less) there abound in fish bones of cod, pollock, wolffish, plaice, haddock, monkfish, lingcod, and of course halibut. All of these were targeted, all formed integral links in human diets, but the halibut alone was venerated in ancient pigments on cave walls, drawn by unknown hands at a time when the world had not yet learned to write.

In Norway today, one probably won’t find anyone worshipping halibut, but one easily finds devotees. By American standards, Norwegians eat a considerable amount of fish (at my house, we eat fish at least several times a week, but never have I consumed as much fish as I did in six days in Norway), and it seems that a great many Norwegians living near the coast enjoy fishing in the fjords (always with handlines, poles being the hallmark of a tourist). Fish still occupies a seemingly unassailable position in the Norwegian diet.

In Norway, as in other ardent fish-eating countries, most people are fastidious about the quality of fish they eat. But Norway is also a country famous for responsible fish farming, so most people have an underlying respect for the benefits of farmed products (thanks to salmon). Perhaps then, it was inevitable that the Norwegian market would respond positively to farmed Norwegian halibut. Today, though Nordic Halibut is marketed throughout the EU and US (with burgeoning sales in southeast Asia), fully half of annual production is still earmarked for the Norwegian market. Norwegian chefs and cooks use it for all the traditional standards, but more and more one sees halibut used in novel ways, especially raw.

One does not think of halibut as a likely candidate for sashimi or nigiri. While flounder occupies a place of honor in the sushi pantheon, the same has never been said for halibut. Because of its size and age, its meat is generally too coarse and its taste too strong, for such a delicate raw treatment. Besides, wild halibut can be host to some parasites, a few of which are not too friendly to the human digestive system. And beyond all of that, wild halibut are not slaughtered and processed in such a way as to make them amenable to raw preparations (ie, stunning usually is at best haphazard, as is bleeding). Farmed halibut has none of these disadvantages. The fish eat a controlled diet, are slaughtered at a smaller size and in such a way as to minimize stress, are bled out entirely, and are processed from slaughter to packaging in less than 30 minutes. Halibut sushi may seem an odd idea, but it is assuredly a delectable one.

Nordic Halibut aims to complement, not replace, wild halibut fisheries. But one can compare wild and farmed halibut only as far as one can compare, for example, wild and farmed pork.

The reasons behind Nordic Halibut’s success in its home market have much less to do with sentiment or national pride, however, than with practicality and applicability. And, to be clear, it has little to do either with any notion of the superiority of one over the other. Nordic Halibut aims to complement, not replace, wild halibut fisheries. But one can compare wild and farmed halibut only as far as one can compare, for example, wild and farmed pork. In other words, from the cook’s and fish-eater’s perspectives, their uses overlap, but they are unique entities.

Connoisseurs might adore mutton, but lamb (slaughtered at around 12 months) is generally held to be superior. A hen (or even a rooster) may be delightful, but most of us want to eat broilers (slaughtered these days before 6 weeks of age). This holds true for most animals that humans eat, including of course, fish. Smaller, younger animals are more tender, with a more delicate texture and subtler taste. With the partial exception of Bluefin Tuna, all fish reach a size beyond which their edibility rapidly decreases.

From hatch to slaughter, the farmed halibut production cycle is approximately five years, whereas wild halibut may live several decades. So while the typical market size of wild halibut may be between ten and 40 kilograms (headed and gutted), the largest farmed halibut rarely ever reaches 15 kilos. The difference between the two is about the same as mature mutton and a young lamb, between fried broiler and fried hen. It is, in other words, significant. So while farmed halibut may be used in place of wild halibut at every turn, it may also be used in recipes that call for smaller white fish and flatfish.

Its attributes in the kitchen notwithstanding, wild halibut as a product is slightly unpredictable. Chalkiness (caused by a buildup of lactic acid as a result of stress near the time of death) is a chronic problem. While it happens with all wild fish to some degree, it is more extreme and problematic in halibut and other flatfish. Farmed halibut are harvested through a multi-step process to calm the fish and make dispatch quick and painless, which significantly lowers lactic acid levels, and thus occurrences of chalkiness. Of course, this process, with its emphasis on both welfare and quality, also produces a superior quality product as well.

Wild halibut must be carefully managed to avoid overfishing, which means seasons and fisheries are strictly limited, as are catches and the number of vessels in the fishery. And of course wild halibut catches are subject to regulators who must ensure that the wild population is being adequately protected. All of this leads to unpredictability in supply and price. Obviously a farm can produce 52 weeks per year, without the price volatility for which the wild market is known.

To return to our land animal analogy, this is roughly the equivalent of farmed and wild pigs. Both are delicious, but while the latter is a delight, it is the former upon which we rely.

Back at Averøy in the Nordic Halibut office, overlooking a fjord with a thousand years of fishing history, is a table set with a bounty of Norwegian seafood — pickled herring, stuffed crabs, smoked salmon, and more. Though I will eventually gorge myself on the whole cornucopia, it is a plate of raw translucent slices of halibut that I attack first.